Special: What is a reduction?

Special: What is a reduction?

- 4 mins One of the original limitations of the braids was that, if the book got too long (~ 1000 interactions), the braid became unreadable. By paying an extraordinary amount of attention one might be able to follow the story and find some interesting passages, but the number of turns soon becomes a problem for keeping one’s focus. Fortunately, we implemented a workaround for this, and we called it reduction.

So, what is a reduction?

Given a list of N interactions and a reduction rate r between 0 and 1, a reduction is a sublist of size rN that resembles the original list. An example is given in the figure below.

As you can see, some interactions have been dropped, but thanks to the fact that interactions usually get repeated a lot, the structure of the chapter is basically the same. Furthermore, the reductions are performed independently for the different chapters, so that the possible loss of information is equally distributed along the book.

The reduction criteria

When performing a reduction there are two basic objectives that one should fulfil. Objective 1 is that the summary of interactions of the reduced history does not change much. If this is enforced, the relative relevance of each character and of each interaction remains similar in the reduced braid.

On the other hand, we want to mantain some sense of locality: if Alice and Bob interact mostly in the beginning of a chapter, it makes no sense that in the reduced braid they are pictured mainly in the middle or at the end. Therefore a simultaneous objective is keeping characters interactions as close as possible to their original location, so that the story the braid tells is not altered by much. We will call this objective 2.

The math behind the reductions

Objective 1 is easy to implement: we compute the summary of interactions of the original chapter and that of the reduced chapter, we normalize them, and we compare them. The objective is to produce a reduction with as little difference in the summary of interactions as possible.

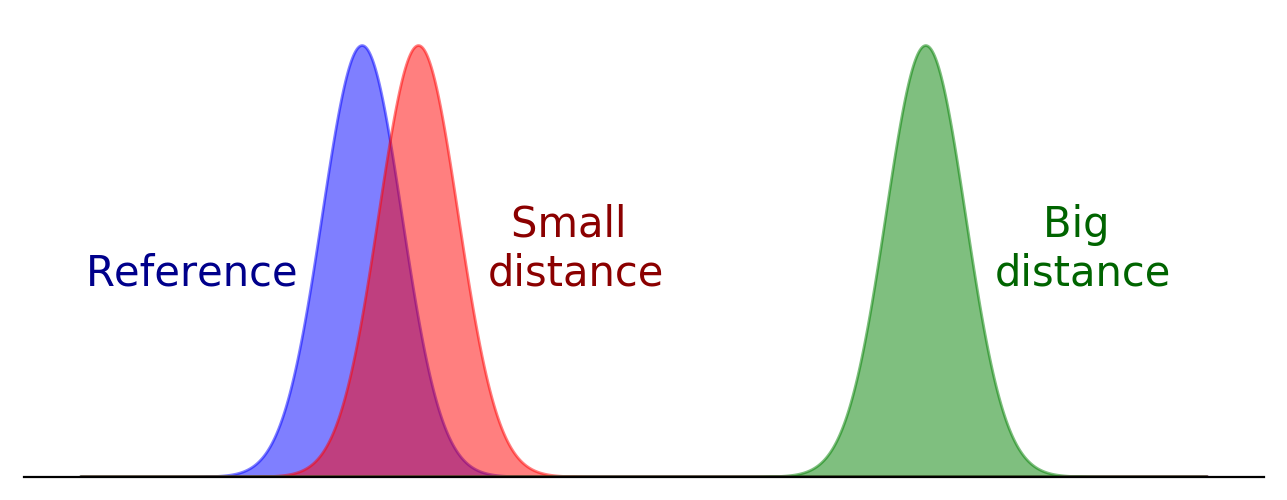

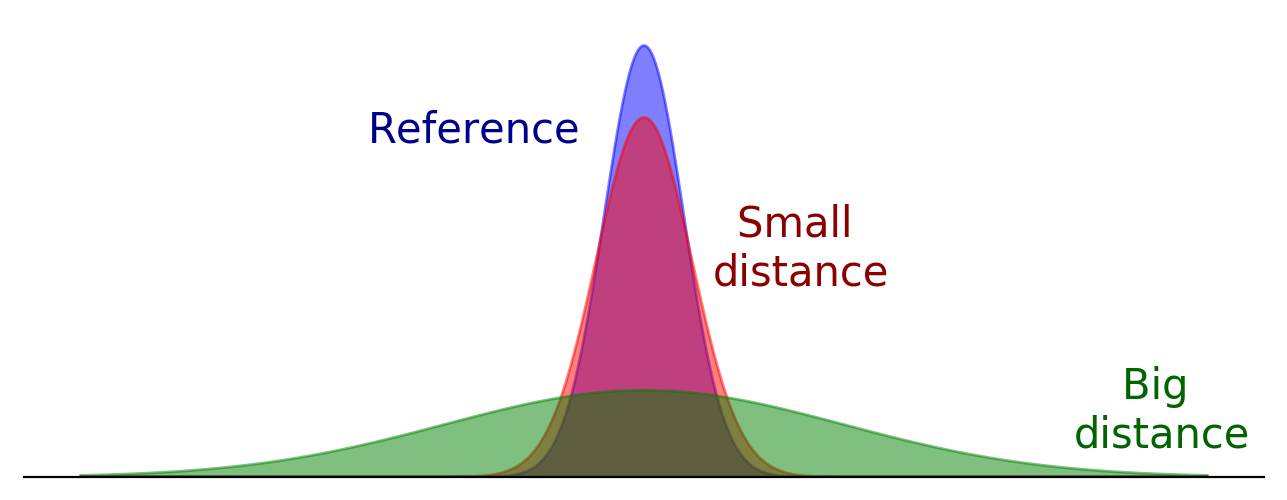

For the second objective, we need to define some kind of distance between histories of interactions, and look for the reduction that minimizes this distance. If we see each history of interactions between two particular characters as probability densities, then a suitable distance is given by the Wasserstein distance. This distance roughly measures how much would it cost to move this shape to this other shape, and that makes it very well suited for our purpose: two shapes that appear very close to the human eye are not too far away in the sense of moving one to the other, and viceversa. If this is not clear, take a look at the following examples:

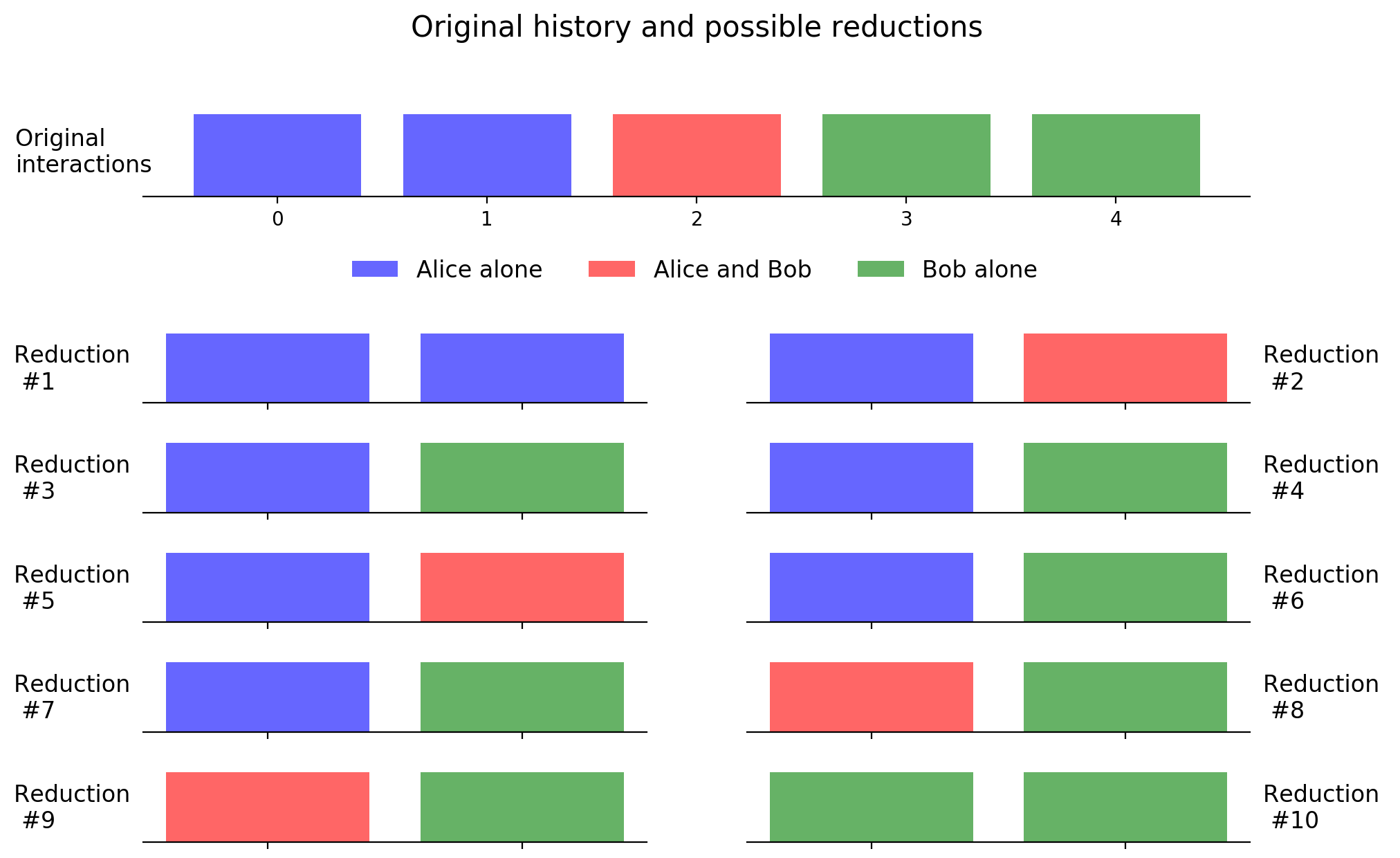

Now that we have all the elements we only have to cycle over all the possible sublists of an original interaction history and look which is the optimum with respect to objectives 1 and 2. For example, for a chapter of 5 interactions and a objective length of 2 interactions, we have the following possibilities:

It seems that #3 (the same as #4,#6,#7) is the best: represents the most frequent interactions of the chapter and mantains their order of appeareance. Of course, we will always lose some interactions, but we expect this to compensate throughout the book.

This approach has a problem, though, and it is that the number of sublists grows exponentially with the original size. For example, for reducing by half a chapter of only 30 interactions we should check 135 million possibilities.

The workaround for this is to randomly sample sublists, and take the optimum over these. We have observed that with 1 million samples per chapter we get a good compromise between CPU time and accuracy, so this is our default value. Appart from this we do some preprocessing to exactly reduce easy parts (for example, if an interaction appears 10 consecutive times, we can just place 5 in the reduced version), which guarantee that at the end we get an accurate reduction of the original braid.

So long for this week’s special. You can always find more at Literary Braid’s Twitter and Instagram.